From northern Virginia, we needn’t go far to see a very different culture than we have in most of the United States. I found udder peace (whoops, my bad) in Amish Country.

I recently spent 3 days in the Pennsylvania Amish Country. It was a strange experience. I was deep in rural agricultural land, but it almost felt like urban. Finding pull offs along roads, finding compositions to photograph, and the ever-present sense of “unwanted attention” were constants.

My trip to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania was just what I needed. Visiting the “Pennsylvania Dutch” is like stepping back into the early 20th Century, driving the backroads at speeds no faster than horse-drawn carriages, stopping for long periods of time just to watch the Amish work their fields with mules (who actually did most of the work, I admit), and taking in the unique smell of natural fertilizer spewing from the their “honey” wagons.

Lancaster County is only a couple hours from my home, and I’ve been thinking all winter that I needed to go up there and experience it again after many years. Having grown up on a farm myself, pastoral settings have always been a favorite of mine. We have a saying in Oklahoma “you can take the boy off the farm, but you can’t take the farm out of the boy.” That’s so true, I think.

In fact, I avoid cities when I can. Even in Lancaster County, I accidentally drove too close to the town of Lancaster on my first day, got caught up in city traffic and strip malls for an hour, and considered for a moment just heading home. “If this is what Amish Country has become, I’m done!”

Luckily, I quickly escaped modern humanity and spent the next 3 days traveling every back road I could find to the north, east, and south from Lancaster. This is where the rich Amish culture lives today, and I was surprised how strong it remains after all these years of American ‘progress.’ The Amish in their horse drawn carriages, farm teams, and foot-powered scooters were common sightings among the beautiful farm lands and buildings of rural Lancaster County. I’ve included a few travel photos below to give you an idea of what I found.

Photographically speaking, I met with several challenges to how I normally work in the field, to the point of giving that up for something else. I normally just pull off and park on the road easement when I find something to photograph, and then take my time setting up and composing the scene. I can be on site like this for half an hour or more.

But road easements in Lancaster County are essentially non-existent except where the rare power line happens to follow the road. Without utility easements, the Amish plant their crops to within a few feet of the road bed, making pulling off the road to photograph impossible. I would never drive onto their crops just to get a picture.

I was able to find and capture “Clear Boundary” (my opening picture) along a road where the easement was wide enough for my van to park safely while I composed the shot. And I didn’t have a lot of time to do that because I had to share the easement with farm machinery pulling over to allow car traffic to pass. Oh, the life of a landscape photographer! :)

The second challenge was that most of what I found that really interested me were scenes that included moving subjects. Things that move have to be photographed quickly, and in many cases repeatedly. That’s not so easy with the large bellows camera that I typically enjoy using.

So after the first full day of empty searching for “normal” situations, I decided to pull out my faster 35mm film camera with a zoom lens attached and just have fun shooting from the van window with butt in seat. These will never become large exhibition prints, but not everything we photograph has to be “serious,” I guess. I thought you might enjoy seeing what I saw.

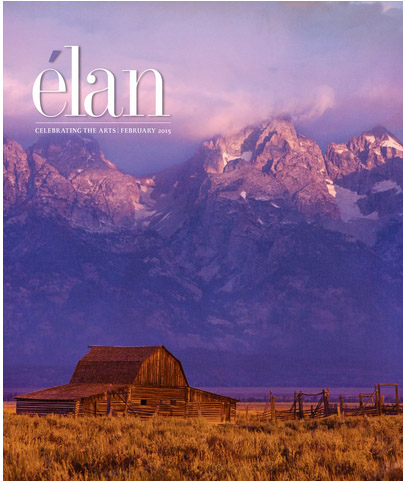

I’ve added two images from the trip to my gallery, and they are now available. The first is “Clear Boundary.” Just click the picture to see it in the gallery. The other scene is “Bifurcations,” a quiet B&W composition of a lone tree reflecting itself in the Pequea River in southern Lancaster County. See it here: “Bifurcations”

More images from Amish Country.

I came upon this massive mushroom this week while out walking on a local farm. It was more than 2 feet in diameter and rested in a bed of clover just at the base of an old dead tree stump.

I came upon this massive mushroom this week while out walking on a local farm. It was more than 2 feet in diameter and rested in a bed of clover just at the base of an old dead tree stump.