Update 3/31/2016

I published this article back in 2011, and at that time I had 3 years experience personally scanning negatives. Add 5 years since, and probably 500 hours scanning, and well, you get the picture.

________________________

This article dispels many myths related to the technical process of scanning negative (print) film. Developing photographers may save themselves time and money and produce higher quality scans by knowing these myths exist.

_____________________________

It bears repeating: Take lessons you read on the internet (or anywhere) with a grain of salt unless it comes with substantiating explanation.

I like reading “tips”, “lessons”, “warnings”, “advise” etc from posters on internet blogs or fora. It helps me understand what others have found to be useful so that I might use this information to solve my own problems. Believe me, growing up in the pre-internet era makes me very thankful that we now have the wealth of information available at our fingertips.

Scanning film is a necessary evil for photographers who choose to use a hybrid workflow, where film is used to capture the image and digital processes are used to produce the final image for sharing or printing. For whatever reason, the art of communicating film scanning techniques by those who choose to do so is like reading early software “user’s manuals”: Users couldn’t understand a word in them. If you’re an electronics engineer, you might find that last statement funny (or not), but it’s still true. But unlike modern software developers who have learned how to communicate clearly to non-technical users, scanner developers have not.

I’ve been scanning color and monochrome negatives for about 3 years, and I think I’ve just about got it down. I can produce a digital scan of a 35mm, 6x7cm, or 4x5inch negative without unacceptable noise having very high resolution, and requiring only minimal corrections in my imaging software. My success isn’t so much due to what I’ve read in the blogs or scanning fora as much as it is about TENACITY. Which brings me to my point: Don’t take for granted that what you read in the blogs means exactly what you think it means or that it even applies to your own photographic situation. This is doubly true if the blogger fails to substantiate (or thoroughly explain) what he/she really means, and ideally includes pros and cons with their recommendation.

Here are examples of myths I’ve read on expert sites that I accepted as truth, didn’t take the time to investigate them on my system using my workflow, and which literally set me back weeks to months in getting to the level of scanning competence that I have currently:

Myth 1. “Scanner manufacturers claim much higher resolution than they can actually deliver, so there is no need to scan above 2400 ppi.” I use an Epson V700 scanner that Epson claims can scan at 6400 optical resolution. It also has a lower resolution lens that can scan at 4800 ppi. Experts have repeatedly scoffed at Epson’s claims, and have consistently recommended not to scan above 2400 ppi because “..you won’t get any better details from the shadows above 2400 ppi.” What I’ve learned in my experience is that while I may not get additional shadow details when scanning at 4800 or 6400 ppi, the digital file produced is much better. I’ve found that with this scanner, when using the OEM negative holders provided to ensure optimal focal point of the higher resolution lens, I do not get what I presume is aliasing in the digital file. The effect I get when scanning at low resolution is best termed ‘blotchy’ –clear blue skies looked like wet cotton candy. When scanning at the optical resolution of one of the lenses, clear blue skies look more like clear blue skies. For whatever reason, forcing the V700 to scan at less than the highest optical resolution for the lenses seems to produce artifacts in the scanned image. Based solely on the quality of the resulting image, I always scan at the highest optical resolution. Yes, this requires more time scanning and more disk space, but it is the technique that produces a result that is minimally acceptable to me. I deal with the disk space requirement by buying more disk space. All of my negatives that don’t deserve printing are later compressed to “proof” resolution and archived at 5 megapixels or so. (I always have the negatives that can be re-scanned if needed.)

Myth 2. “Scan at the minimum resolution for your intended purpose and do not compress the file.” Update: I no longer consider this to be a myth..I’ve found it to be a good practice. But since my intended purpose is to make really large prints, I’m always scanning at maximum resolution to get the largest file size I can.

Myth 3. “Don’t use the scanner software to set the contrast levels or balance the color; do these tasks in your image processing software instead.” Again, until I investigated this, I abided by the expert advice and then fought the losing battle of adjusting the levels and colors in Photoshop or Lightroom without ruining the quality of the image. The result was excessive artifacts, noise, and artistic frustration painted all over the images. What these experts must presume is that every negative is perfectly exposed and taken in the best lighting God can make. As a landscape photographer, such circumstances are very rare. I typically express images that have wide latitude (meaning deep blacks and paper white highlights). If a negative has no such attributes, I will adjust the contrast to produce them. Whoops…adjust too much and the histogram will look moth-eaten and introduce compression artifacts in the image. The more you adjust, the worse it gets. What I’ve found works best is to get really close to the final image contrast and color balance using the scanner software. This means much less fidgeting in post-process and fewer artifacts in the final image. Update: I still find that the scanner algorithms for converting the continuous tones of a negative into digital bits is better than how Photograph CS5 or Lightroom 4.0 converts one tone to another. Even my 1980s-era Howtek 4500 drum scanner does a better job than CS5 or LR at setting levels, white/black point, and perhaps even curves.

As an example, the two images below are from the same negative. The left image is straight from the scanner without any post processing; the right image received minor enhancements to adjust local and global contrast, saturation, and highlighting. No artifacts resulted from the post-processing. The negative was captured using a Nikon F5 onto Kodak Portra 400 film. I scanned the 35mm negative at 4800 ppi using VueScan with no compression. This produced a 30 megapixel image file. In Vuescan, I locked the film base color to neutral black and the image color to neutral white. Modest post-processing included cropping, adjustment to both global and local contrast, minor sharpening (but no output sharpening), and targeted adjustments to brightness and contrast to the foliage and water. The full resolution image has no processing artifacts that I can see at 100% zoom.

If you find yourself fighting your post-processing technique on flat, low contrast scanned negatives produced using the common expert recommendations, then break the rules. Set levels and color balance in the scanner software and see for yourself if the final result is better.

Myth 4. “Scanning wet mounts will result in higher quality scans.” Well, I tried this and found no difference in quality of the resulting scan, just a lot of additional work and cost. The scans I get using Epson V700 negative carriers, scanned at 4800 ppi, have the same detail in the shadows, the same detail in the highlights, and have the same latitude as those scanned using KAMI wet mount system. I did note that I didn’t have the dust problems when using KAMI, but otherwise I noted no improvements. Update: My main scanner is now a drum scanner, which requires wet mounting, so of course that’s what I do. I think the point should be made that sometimes, you need to do what you need to do. If you have a terrible dust problem in your scanning workstation, you may find wet mounting really helps, and may be essential. There is a far greater difference between a CMOS scanner (desktop scanner) and a PMT (drum) scanner then there is between wet mounting and dry mounting.

Myth 5. “Amateurs use negative (print) film and professionals use transparency (slide) film.” The implication here is that transparency film somehow has qualities that so far surpass print film to make print film significantly inferior. Such statements could lead developing photographers to adopt the use of transparency film without even exploring what I consider to be the strong points of print film. When I decided to begin shooting color about 4 years ago, I made the decision to use print film precisely for the reasons most “experts” claim as its weaknesses: exposure latitude and development latitude.

Transparency film typically has a 4-5 stop exposure latitude, about the same as most 2005-era digital cameras could detect. In landscape photography, a typical scene can deliver brightness ranges spanning 8, 9, or even 10 stops or more. This means that the photographer has to decide at the time of capture, whether to clip the shadows and lose most low light detail or to clip the highlights. Digital photographers are well aware of this situation; most digital sensors also have latitude limitations that result in ‘blown out highlights” or “dumped shadows.” Fortunately for digital photographers, the technology is improving as new sensors are invented.

Print film has no such limitations. In fact, print film can capture the thinnest density having detail on the negative (i.e., the deepest shadows of a scene) while also capturing fine details in the most dense areas (i.e., bright whites like sun lit clouds). Easily.

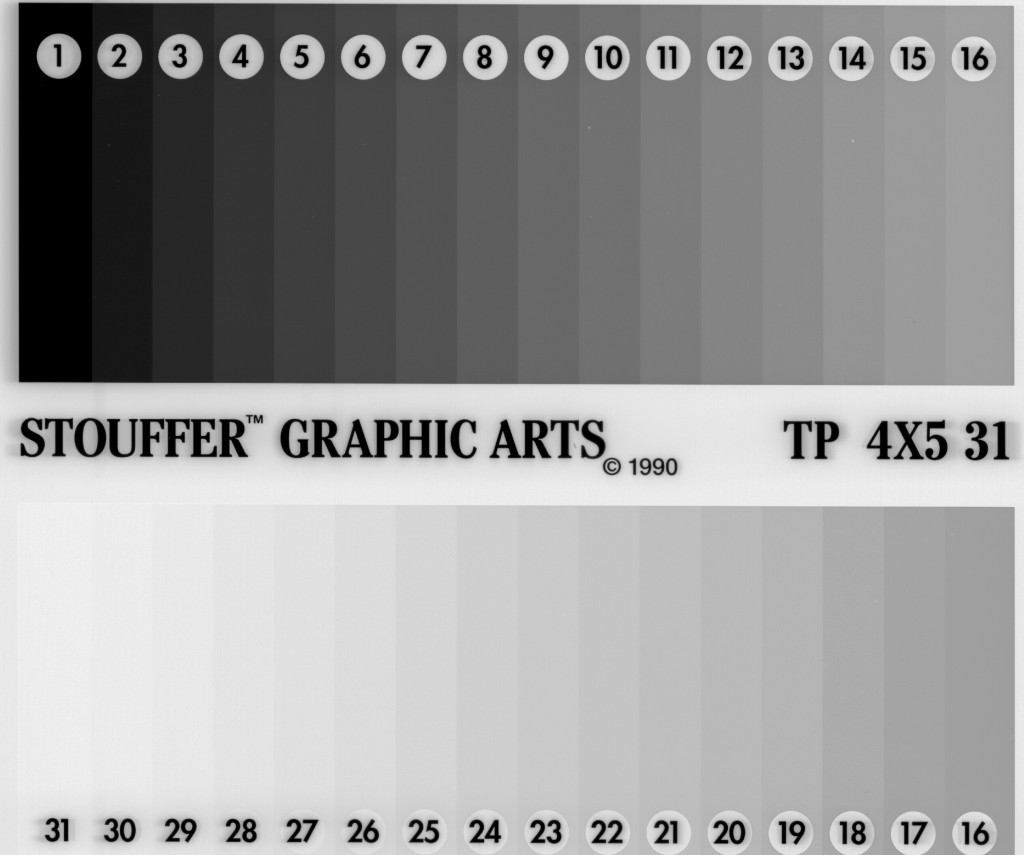

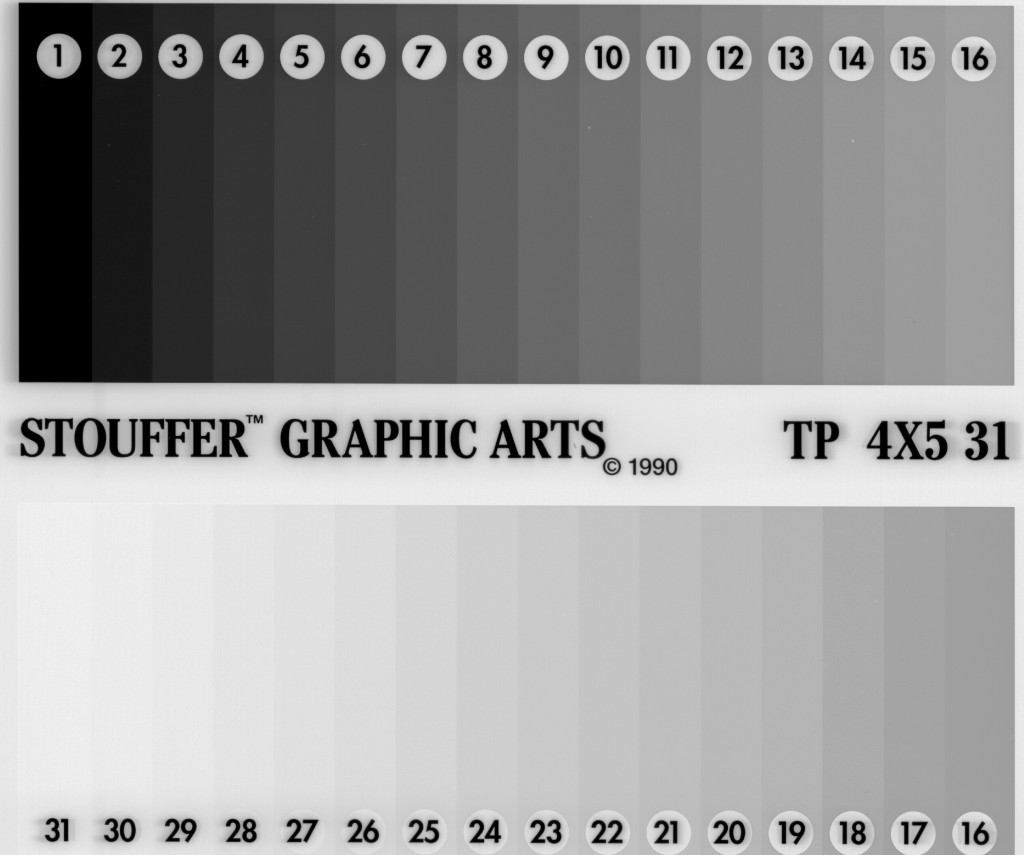

Scanners of the qualify of my Epson V700 also have a very wide latitude of detection. The figure below is a scan of a 31-step density wedge made on the Epson V700. Each step is 1/3 of a stop from its nearest neighbor, so from one end of the strip to the other is 10 stops. When I scan this step wedge as in the figure below, I can easily detect 31 distinct steps, indicating that the V700 has a detection latitude somewhat over 10 stops.

As a practical example, the scene below presented me an extreme range of brightness. This range had to be captured in one shutter click due to movement of the water, the geyser eruptions, and the sun. Then, the scanner had to detect detail in both the sun and the shadows among the foreground grasses. The picture was captured using Kodak Portra 400 film, with no neutral density gradient filters used. I developed the film normally. The original scan retained detail/color in the sun spot and the shadows concurrently. If I had captured this using a digital camera or if I had used transparency film, this scene would have required multiple shots and later processed using HDR techniques and/or by compositing multiple images, which can introduce their own artifacts in the final image. Shooting with print film gave me the exposure latitude I needed to capture this scene.

I admit to never using slide film for my artistic work, so my experience is limited. However based on the knowledge that slide film has a much narrower latitude and my own experience using print film with its proven (in my hands) wide latitude, I completely dismiss expert contentions that “professionals should use transparency film while amateurs use print film”. Don’t hesitate to use print film seriously. I’ve found that much of my landscape and nature images require the exposure latitude that only print film can deliver.

If this article helps you decide to try scanning print film or if it simplifies problems you’ve had in your scanning techniques, then it accomplishes its purpose. While the internet forums are full of information, take what you read with a grain of salt. The information is only accurate in the hands of the writer and may not relate one bit to your situation. If you have the time to test such advice, that would be a wise decision. It just may save you a lot of time and money.

Update: To be serious photographers, we have to invest in equipment we need. We need to learn the techniques that are important to our craft. I’ve never been one to collaborate with others in creating my photographs, and that means outside film scanners, printers, etc. If you want to use the hybrid workflow, then go ahead and invest in a scanner, learn to use it, spend the time testing various ways to get the job done using the equipment you have. At the least, the growing interest in film photography these days means a growing market for used equipment, so you can always sell the scanner later if you decide scanning is not for you!

J Riley Stewart