Establishing provenance for fine art photography is just as important as provenance for paintings and other hand-crafted visual artworks. Let me tell you why and how to determine if a photographic print is original.

I recently read a story about a gallery customer who bought an Ansel Adams photograph on the cheap ($6). He was elated, believing it to be an original. But, when he later discovered it was merely a cheap reproduction from a calendar, he felt cheated. You can read about it here: http://petapixel.com/2014/10/07/print-scam-meets-eye-ansel-adams-gallery/

This buyer isn’t the first–and he won’t be the last–to be confused about the definition of “original photograph.” With a little bit of knowledge, and understanding the terms used to describe art originality, you will be a smarter collector.

It’s fairly easy to identify an original oil painting. You can actually see the paint on the canvas. It’s not so easy to tell original watercolors or illustrations from their reproductions. Printing materials today are so good that, without advanced inspection, a reproduction of a watercolor or illustration can look very much like an original.

Fortunately, when painters and illustrators sell printed copies of their artwork, they usually mark them as “reproduction.” Reproductions are made using a variety of mass printing processes, such as digital inkjet or lithographic printing. Anytime you see contemporary wall art marked as a reproduction, you’re looking at a mechanically printed digital picture of the original handcrafted artwork, and there may have been thousands of copies made. Because of this, reproduction prints are much less expensive than the original artwork.

Well, if digital prints of paintings are considered reproductions, why aren’t all prints considered reproductions? Aren’t modern inkjet photographic prints just copies of a digital image?

It’s true that today the vast majority of photographic prints are created using mechanical printers. And the number of copies is virtually limitless with today’s printing capabilities. This situation makes defining “original photograph” much more useful today compared to the times when photographers made “copies” in very small numbers and when each print was hand made from an original piece of film.

Uniqueness has never been a strict criterion for describing art as original. A painter or illustrator can create the same scene again and again, a songwriter can record the same song again and again, and a photographer can print her photograph again and again. Art need not be “one-of-a-kind” to be original.

There is, however, one attribute that all artwork must have to be universally recognized as original: provenance. This includes all visual artistic media, even art photographs.

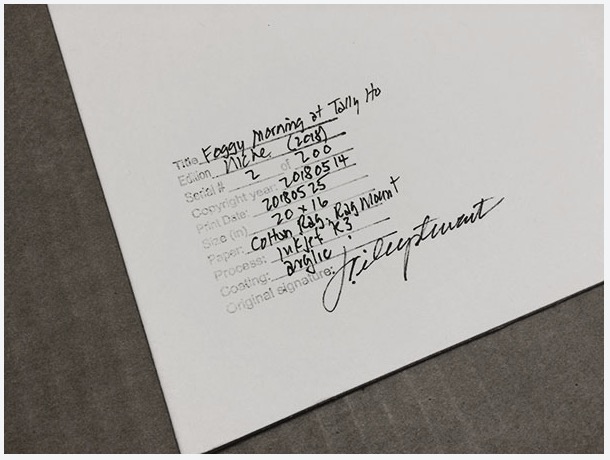

Provenance is a set of facts that inextricably link the physical object of art to its creator. Provenance describes the artwork explicitly, disclosing its title, the name of the artist, the date of creation, its medium, and its dimensions, at the very least. The medium will indicate whether the artwork is an oil painting, a bronze statue, or a photograph. When you see provenance on a label or caption, you can be fairly confident that the physical object is authentic to the named artist. When you don’t see provenance, it either means the artist neglected to document his/her creation or that it’s a reproduction or a forgery, none of which is good for you as a collector.

Original photographs, i.e., those with provenance, carry another descriptor that isn’t as commonly used in handcrafted art: the copyright status at the time of creation. The creator of any artwork is always the first owner of the copyright. Copyright ownership is especially important to the provenance of original art produced through a printing process like photography, digital art, printmaking, stories, and songs, where copyright status is almost always cited in the provenance.

Like paintings, the opposite of an original photograph is a forged photograph. Today it’s fairly easy to download someone else’s photograph from the web, run it though editing software, print, sign it, and then frame it for personal or commercial use. Clearly, when someone claims someone else’s photograph as their own, that photograph is not an original. It’s a forgery. Of course, this violates the law, but it can and does happen. Should a buyer of a forgery expect to pay the same price as an original? Of course not. Do they? Sometimes, but only when deceived or uninformed.

Here’s some of the most common ways to determine originality of an photographic print:

- Original photographic prints will have provenance, including copyright information, typically documented on a Certificate of Authenticity (COA). The COA will be either attached to the photograph itself or in the hands of the gallerist selling the photograph. It should always convey with the photograph upon sale.

- Know the photographer. Research his/her website, visit their gallery, and communicate with them. They will be happy to discuss a particular piece with you and substantiate it as their own, and tell you when it’s not. A part of being a professional art photographer is documenting provenance for each original work.

- Read the label. If you see a photographic print labeled as a “reproduction,” it typically means that the authoring photographer had very little to do with the printing, distribution, and selling of that photograph (either legally or illegally). Ansel Adams himself had nothing to do with the printing and sale of the 2013 calendar print mentioned in my lead paragraph, and the label correctly identified it as a “reproduction.”

- Finally, give yourself permission to accept that if the photograph looks like it came from low quality printing like a book, poster, or calendar or is priced at $6.99, it is very likely a reproduction.

I take a rather rigid approach to provenance for my own work. My original prints all have a common description: I took the picture and own the copyright, I personally interpreted the scene/subject, I personally printed the photograph using techniques I deliberately chose, and then finished the photograph and documented its serial number in a limited edition. Each of my originals comes with a signed COA, either as an attachment or permanently stamped on the reverse of the print, that should follow the photograph forever.

More about how I manage my limited editions of fine art photographs.

If you collect artwork and care about potential resale value or collectible status, it’s smart to know when you’re collecting originals versus reproductions. You don’t want to pay original prices for reproductions, and if you ever choose to resell your collection, don’t expect someone else to have great interest in your reproductions.

Happy collecting!

I came upon this massive mushroom this week while out walking on a local farm. It was more than 2 feet in diameter and rested in a bed of clover just at the base of an old dead tree stump.

I came upon this massive mushroom this week while out walking on a local farm. It was more than 2 feet in diameter and rested in a bed of clover just at the base of an old dead tree stump.