Color affects our emotions. Whole volumes have been written describing these effects, and how artists and advertisers use color to best induce specific emotions. Color also has profound effects on the perceived depth of any two-dimensional representation of our three-dimensional world.

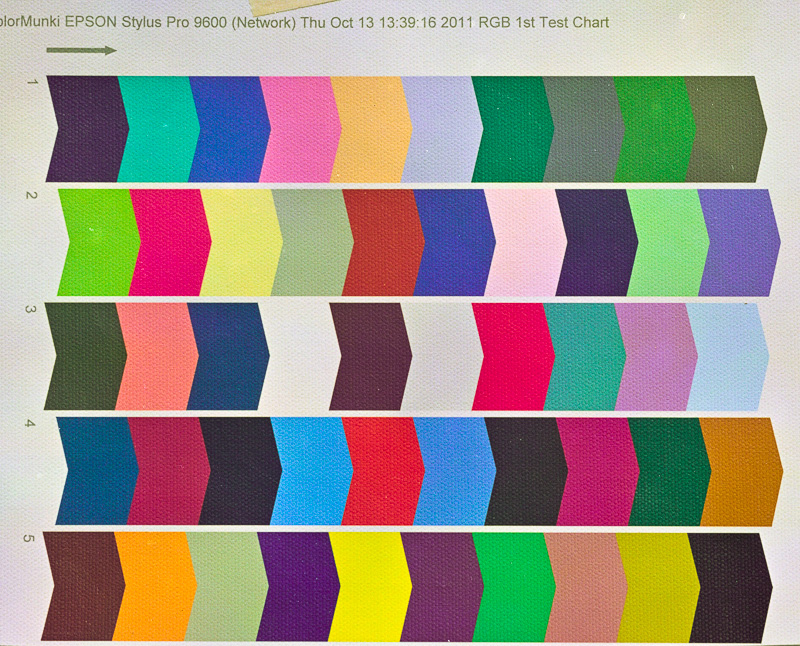

To make the point, look at the three squares below. Which color, blue or red, seems ‘closer’ to you? This example is a good way to show how our eyes play tricks on us when it comes to color alone. If you see the red square appear to be in front of the blue squares, that is the typical response. There is a biological explanation for this effect, but the result is that “warm (e.g., red) colors project” and “cool (e.g., blue) colors recede.”

How does this relate to the psychology of B&W (so called, “monochrome”) prints?

I’ve been creating B&W prints for years, but the truth is, I don’t really care for “black and white” prints. I much prefer “purple and white” or “eggplant and white,” and for some subjects, “brown and white.”

The 20th Century masters of landscape photography touted the physical and emotional effects of toning their B&W prints. There were dozens of techniques and materials used to impart colors selectively to silver gelatin prints. Among the most widely used was a selenium chloride solution. Depending on the paper and developer used to print the image, bathing the print in a weak solution of selenium chloride for a few minutes materially changed the color of the print to what Ansel Adams called an “eggplant” color, most noticeable in the darker shadow areas.

I loved the aesthetic effect selenium toning had on my prints, so it became a standard part of my darkroom workflow, and now continues in my hybrid workflow.

What was that effect?

Take a look at the two images below. The first is a straight “monochrome” depiction of Blackwater Falls in West Virginia. It’s a beautiful image, full of light and excitement and depth. These characteristics are imparted solely by the subjects, which are entirely shades of neutral gray (you may see color, but it’s because your monitor is not neutral–most are not). This depiction represents what comes out of the standard B&W developer or when you convert an image to B&W in a digital workflow.

Now look at the second image. It was given a treatment that selectively toned the shadow areas as if the print was toned in my darkroom method for selenium toning. The mid tones and shadow areas now have this deep purple (so called “eggplant”) tone.

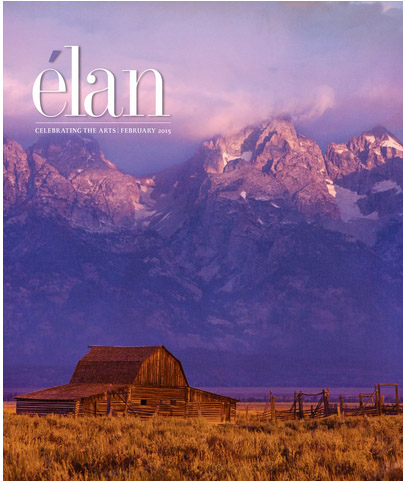

There are many other tones besides the ‘eggplant’ of selenium toner that artists can choose to use. For some images, I like a warmer tone that mimics Kodak Brown Toner I used to use on wet prints made in the darkroom. Brown toner is very effective in giving a more nostalgic aesthetic to some subjects, such as those in my Virginia Grist Project and other old architectural subjects, like “Dappled Shadows” below.

How do you feel about the two different presentations? If the second image appears to have more depth in the shadows, it’s because the cooler purple color appears to recede behind the screen surface; the comparatively warmer whites appear to be in front of the shadows. This therefore tends to push the highlights in the water forward and causes the trees and other shadows to fall back into the image, much like the red and blue squares above, creating a greater sense of depth in the image. Depth in a two-dimensional picture encourages the viewer to want to engage in the picture, something all visual artists want from our audience.

There is also an emotional aspect to the image I think is important. Hues in the purple range are known to induce a sense of calm and creativity, of wonder and exploration. Purple is a very emotional color to most humans. The toned image of this enormous waterfall therefore creates an internal conflict that is very subtle, but still there. First, you stand before this potentially dangerous, powerful, noisy waterfall that most of us react to with a bit of anxiety, red flags goes up in your consciousness: beware! But surrounding the waterfall on all aspects is this calming tone that encourages exploration of the shoreline, the trees, the flowers and rocks along the river’s banks. This is a conceptual contrast, and one I think adds drama and excitement in the toned print that isn’t so apparent in the untoned print.

I always tone my B&W prints, varying between a cooler (more bluish) to a warmer (more reddish) selenium tone, depending on the subject of the photograph. It’s always a very subtle tone, not even as much as I’ve shown you in the second image above, which I exaggerated for purposes of this article.

If you make B&W prints (or even web images), experiment with toning to emphasize the feelings you want to compel in viewers. There is a infinite number of possibilities. In Lightroom, use the Split Toning feature to do this. For the toned image above, I set the Highlight toning saturation to 0 and the Shadow saturation to 9, hue 354. I set Balance to +50, favoring toning to the shadows.

To my heart, monochrome images should be way more than black and white!

Do you already tone your B&W images? What are your experiences? Let me hear your thoughts.

Cheers!